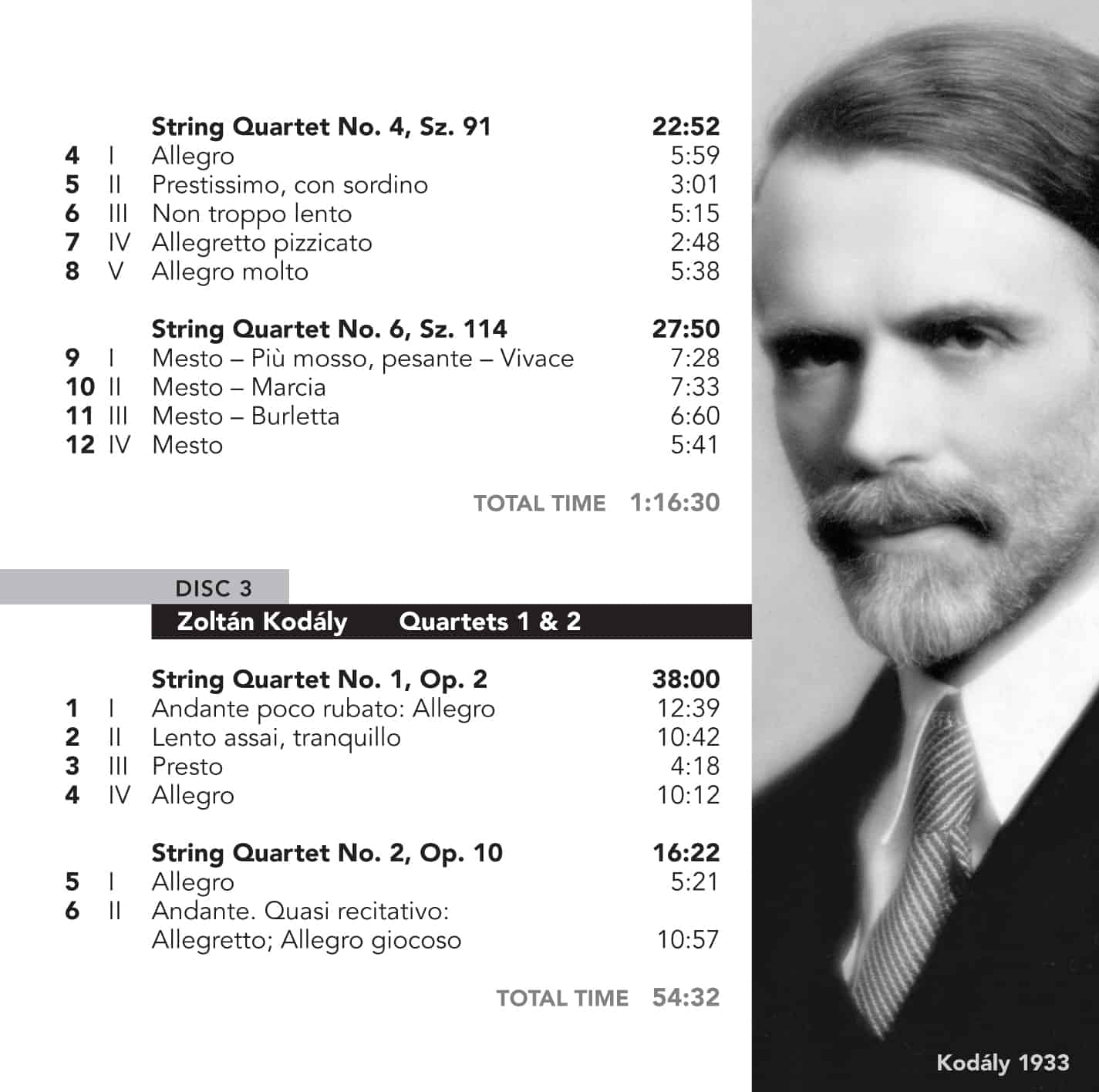

Zoltán Kodály composed his First String Quartet in 1909, when he was 27. Four years earlier, Kodály and Bartók had embarked on their first joint expedition to collect Hungarian folk songs, and now Kodály began to incorporate the melodies, rhythms, and shapes of that music into his own compositions. The First String Quartet — at forty minutes long, a substantial work — is one of his earliest compositions to show this influence.

Zoltán Kodály composed his First String Quartet in 1909, when he was 27. Four years earlier, Kodály and Bartók had embarked on their first joint expedition to collect Hungarian folk songs, and now Kodály began to incorporate the melodies, rhythms, and shapes of that music into his own compositions. The First String Quartet — at forty minutes long, a substantial work — is one of his earliest compositions to show this influence.

The first movement opens with an introductory Andante poco rubato dominated by the cello’s long song, which will furnish the quartet’s fundamental material. This theme, built on shifting meters, is derived from an old Hungarian folk song with the first line Lement a nap a maga járásán. It may be useful to know the text of that song:

The sun has gone down in its own true course.

A golden oriole calls on the Tisza riverbank,

A golden oriole and a nightingale.

My darling is lovely — how can I part from her?

When I die, they’ll bear me to the graveyard.

They’ll place a wooden cross upon my grave.

Come out to me on a moonlit evening.

Fling yourself down against my grave marker.

At the Allegro the upward sweep of the cello’s theme restates the song’s melody in a slightly modified form. This movement is in sonata form, and when the more lyric second theme, marked Poco sostenuto, arrives in the first violin, it too is revealed as a variation on the cello’s opening song.

After a brief introduction, the second movement takes shape around the first violin’s long opening melody in 9/8, itself a derivation of the cello’s statement at the beginning of the quartet. Kodály builds this movement on several fugato extensions of that theme, and along the way the pizzicato cello reprises the shape of the original song. The third movement, marked Presto, is the quartet’s scherzo. Its racing opening section gives way to a Più moderato central episode built on a long duo for viola and cello. A return of the opening material rushes this movement to a vigorous close.

The last movement is in variation form, but it opens with a re-visiting of material heard earlier in the quartet. Only when this is complete does Kodály announce his basic theme, marked Allegretto semplice and played by the first violin over steady accompaniment. There follow eight variations, most of them at quick tempos. A charming story about this movement: the composer’s wife Emma wrote the fifth variation, a spirited Allegretto in 5/8, and in a footnote in the score Kodály gave her full credit for the variation. The First String Quartet concludes with a Presto coda.

This music — youthful, vigorous, and flavored with Hungarian inflections — seems entirely normal to us today. It is the work of a young composer heir to the classical tradition and finding a voice of his own in the folk material of his own country. Yet it went straight up the noses of the conservative music critics in Budapest. In his study of Kodály’s music, László Eösze quotes several of these reviews. One critic denounced Kodály “for holding both thought and melody in contempt,” while another declared that while Kodály was responsible for teaching harmony at the Academy, “he completely shunned it in his own work.” Another critic denounced Kodály as “a deliberate heretic.”

A century later, we may smile at these statements, but their language and fury suggest some of the atmosphere that Kodály, Bartók, and the Waldbauer-Kerpely Quartet were forced to confront during the first decade of the twentieth century.

| iTunes | Allegro Classical | Amazon |