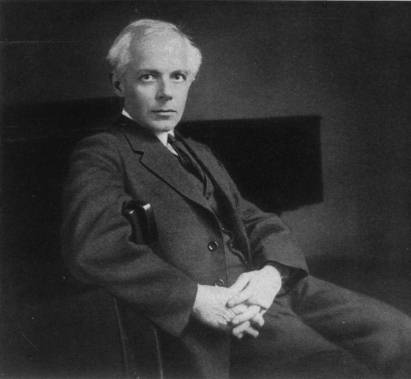

In 1973 Benjamin Britten—frail and facing a heart operation— composed his final opera, Death in Venice. Based on Thomas Mann’s 1913 novella, the opera summed up many of the themes of Britten’s artistic career: as the aging novelist Aschenbach embarks on a quest for spiritual redemption in a city assaulted by the plague, he is torn between his search for beauty and the corrupting force of his own physical desires. Two years later, in the fall of 1975, Britten composed his String Quartet No. 3. It would be (except for a short choral piece for children) his final composition, for Britten died of heart failure the following year. The Amadeus Quartet gave the official premiere of this quartet on December 19, 1976, two weeks after the composer’s death, though Britten had heard this music played through shortly after he completed it.

In the course of composing the quartet, Britten returned to Venice—a city he loved—and in fact he composed the quartet’s final movement there. Inevitably, that visit reawakened memories of his opera, and this quartet makes explicit references to Death in Venice: specific themes, key relationships, and mottos that had appeared in the opera return in the quartet. This all raises a question: does one need to know Death in Venice to understand the Quartet No. 3? The answer to that question must be no—this quartet will stand on its own merits—but it may help to know that this was Britten’s final instrumental work and that it draws on music about a spiritual quest.

The String Quartet in a Time of War:

Benjamin Britten and His Contemporaries

Sunday, May 21, 2017 – 2:00pm

Vanderhoef Studio Theatre

Mondavi Arts Center

TICKETS

Sunday, May 21, 2017 – 7:00pm

Vanderhoef Studio Theatre

Mondavi Arts Center

TICKETS

The String Quartet No. 3 is in five unrelated movements, and Britten at first thought of titling this music Divertimento rather than Quartet; he finally became convinced that it had sufficient unity and seriousness to merit the latter name. Though Britten’s Third String Quartet does not sound like Bartók, it has some of the same arch-structure favored by the Hungarian master: the three odd-numbered movements are at slower tempos, while the two even-numbered movements are fast. Each of the five movements has a descriptive title. The opening Duets is built on a series of pairings of instruments in different combinations, beginning with the rocking, pulsing duet of second violin and viola. The movement, in ternary form, offers a more animated central episode. Ostinato, marked “very fast,” drives along a ground built on a sequence of leaping sevenths; lyric interludes intrude into this violence, and the movement eventually comes to a poised close. The title of the third movement, Solo, refers to the central role of the first violin, which has the melodic interest here, often above minimal accompaniment from the other three voices far below. Britten marks the opening “smooth and expressive,” but the central sequence is cadenza-like in its virtuosity; the movement comes to a calm close on a widely-spaced C-major chord. In sharp contrast, the Burlesque is all violent activity, and this movement has reminded more than one observer of the music of Britten’s good friend Shostakovich. Longest of the movements, the finale also has the most unusual structure. It begins with a Recitative that recalls a number of themes from Death in Venice, and after these intensive reminders, the music settles into radiant E major (a key identified with the figure of Aschenbach in the opera), and the first violin launches the gentle Passacaglia theme of the final section. Britten marks this cantabile and names this section La Serenissima. That sounds like a conscious invocation of Beethoven, who gave the finale of his String Quartet in B-flat Major, Op. 18, No. 6 the title La Malinconia, but here it refers to the musical motto associated with the city of Venice in Britten’s opera. The Passacaglia proceeds calmly to its close, where the ambiguous concluding chord dissolves as the upper three voices fade away, leaving the cello’s deep D to continue alone and then drift softly into silence. Britten’s comment on this ending was succinct: “I wanted the work to end with a question.”

—Eric Bromberger